Anxiety has been part of my life long before I even knew that word existed. The extreme fear I felt at age six when I couldn’t finish writing down school lectures and I knew my grandmother was gonna beat me up once I got home. The shame I felt upon being teased by childhood friends for not knowing how to ride a bike, so much so that I refused to show my face even when they genuinely wanted to teach me. Running away from basketball activities in high school because I didn’t want them to know that I sucked. The looming fear that the friends I somehow made in hip-hop would one day shun me as a fraud. The unnecessary panic to please my ex that prevented me from being truly mentally present in situations — an issue that had constantly plagued and soured our relationship.

In therapy, it was suspected that I had symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, though I’d never finish the program due to big, chaotic life changes from moving abroad, and I’m still waiting for my life situation to stabilize so I can continue to seek help.

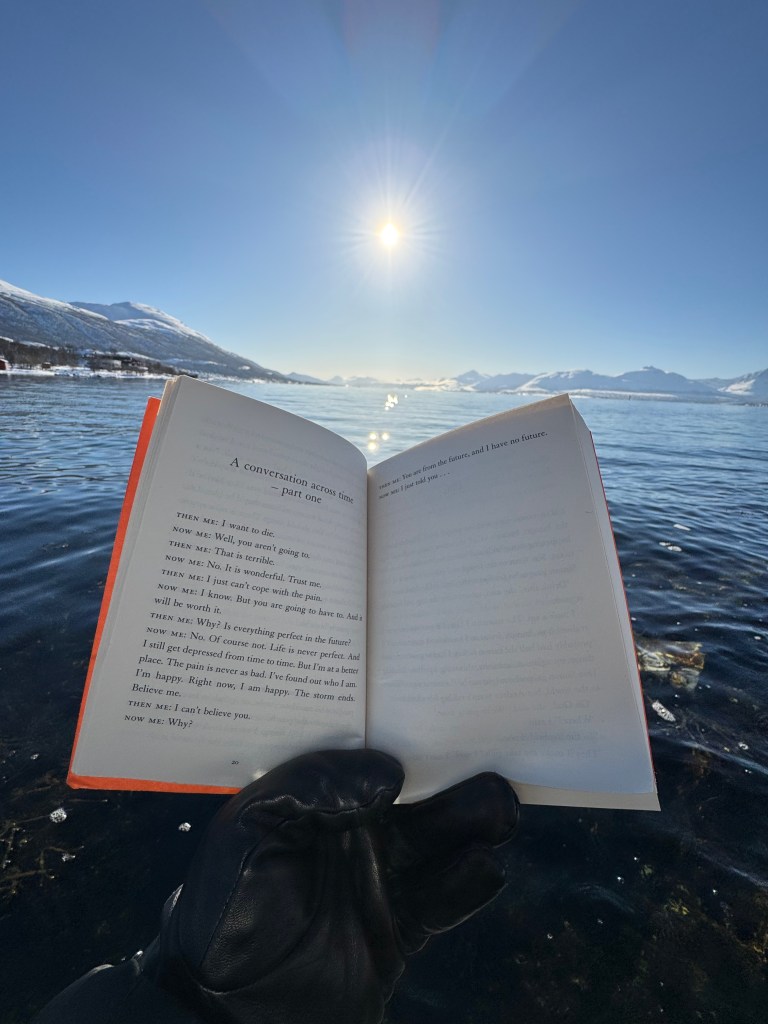

Depression, however, is a word I don’t take lightly, and have refused to associate with myself out of respect to friends who I know have suffered from it. It’s only recently — while processing my breakup with said ex — that the word has genuinely struck a chord with me. After seeing her for the last time at the airport (bless her heart forever), I impulsively traveled to Malta’s Blue Grotto to do some soul-searching. As I marveled at its beauty, I felt this irresistible urge to walk towards the edge, like the sea itself was calling for me; its crashing waves akin to fingertips gesturing: come join us down here.

As someone terrified of heights, that was the most comfortable I’ve ever been staring at certain death below my feet. It just seemed so beautiful to be part of that endless blue. Fear and sensibility would prevail, but I feel like part of me died that day, and I’ve been walking without a soul ever since.

It was days later that I would stumble upon Matt’s book in a gaming convention (that for some reason had a book sale). The title appealed to me because it felt inviting yet unassertive: like the book found me right when I needed it the most, and it knows exactly what I’m searching for, yet it won’t sales-talk me to buy into sociopathic views on life, which is why I hesitate to get into self-help books in general.

I kept the book with me at all times like a lucky charm, though I wouldn’t actually read it until several months later, when I hit my lowest depressive state and genuinely needed to find reasons to stay alive. And what I found… was a friend who had suffered far worse than I could ever imagine, but made my suffering feel valid, and reassured me that things will get better. Or at least it’d feel like it.

The Book

“Reasons to Stay Alive” is a novel / memoir written by the English author Matt Haig, where he opens up about his experiences living with severe depression and anxiety. He begins his story from one fateful day in Ibiza, 1999, where he would start experiencing extreme bouts of anxiety at age 24. His symptoms included shaking hands, heart palpitations, panic attacks, tingling sensations, inability to sleep — hitting him so suddenly and so unbearably that it would trigger constant suicidal thoughts. These afflictions would terrorize him nearly 24 hours a day and completely disrupt his life, to the point where he couldn’t even go outside his house without being accompanied by his girlfriend Andrea.

Given how little we knew about mental health in the 90s, his suffering was compounded by the fact that he couldn’t even comprehend what was happening to him or why. To him, it felt simply like he was losing his mind, and the thought of being seen as such — and being unable to make people understand what was really going on inside his head — made him even more anxious, so he tried his damnedest to appear normal despite the invisible hell that was consuming him.

Luckily for him, he had the most understanding family and the most patient partner, who would support him every step of the way as he battled with his condition and take gradual steps to reclaim his life.

The book is split into five chapters: Falling, Landing, Rising, Living, Being. Each chapter would consist of various anecdotes connected to those four phases of his life, various notes and pep talks to self, journal entries, and studies he had read during his journey to understand his condition. Some of the ideas he’d bring forward through this book include:

- The stigma involved with depression, and the various invalidating remarks made by society to disregard how severely it affects people underneath the surface.

- That depression should not be classified as a purely psychological disorder when it has a very clear physical and neurological affect on the people suffering from it.

- The relative infancy of mental health studies and neuroscience, and how much more we still need to understand about the brain even now.

- The patriarchal society that drives women to depression, but also creates a stigma for men preventing them from seeking professional help and properly dealing with their emotions. Which may be why even though more women suffer depression, men are three times more likely to commit suicide than women.

- How the rapid digitalization and increasing complexities of modern life are overwhelming our brains because our biological hardware cannot evolve at the same pace as technology. We still have our caveman brains with us even as we’re nearing the precipice of a high-tech dystopian future.

- The way capitalism preys upon depressives, subconsciously aggravating underlying insecurities and selling you the idea that buying certain products will magically make you feel better.

- How slowing down and calming the mind can help with anxiety.

- How physically and mentally enriching activities like running, exercise, yoga, meditation, and a good diet can help regulate our hormones for the better. If you’ve always hated hearing this advice from gym bros (like I did long ago), I have bad news for you: science says they have a point.

The loose structure and pacing of the book felt like an organic look into an anxious person’s mind; I see a lot of my own thought processes in Matt’s story. Some days you just jump from one train of thought to another, the connecting threads not making sense even to yourself. Some days go by like a blur, completely uneventful. Some days are so bad, it’s like your brain just wants to delete the painful details and only retain the takeaways. Some days, you remember beat per beat because of how traumatic or insightful they are.

The many short stories really help highlight the longer ones. You can really feel how big of a deal it is when Matt has breakthroughs like the first time he tried to buy groceries alone — his anxious terror palpable through that story with how vividly he describes the waves of emotions he felt jumping from one situation to another; his heartbeat booming so loudly, he can barely hear himself think. It gets very uncomfortable as the pages just never seem to end, so you’re right there with him as he breathes a sigh of relief when it’s all over, never mind that he forgot several items on his bucket list because of the panic to get out.

Anxiety is a tree with deep roots

One part of Matt’s story that really resonated with me was the introspection and exploration of: where did these symptoms begin? What were the earliest signs, and what was the tipping point? One core memory he would share is when he had to make an important presentation for a college course. He acknowledges that the topic itself wasn’t really that hard, but for some reason, he felt so irrationally nervous about it. He would spiral out of control, almost sabotaging himself by getting drunk mere moments before he had to deliver the presentation.

While there were other earlier signs in his life, this story stuck out because it was the first instance that anxiety got in the way of his life in a real, tangible way; the feeling so unpleasant, all common sense flew out of the window in his attempts to get rid of it.

For me, my earliest core memory of losing to anxiety was back when I was around 8 to 9 years old. My town’s local grocery store held a weekly drawing contest for kids, which my grandma made me join. While I liked to draw alone, drawing with a bunch of other kids who were clearly better than me triggered immense feelings of inferiority. By the third or fourth time I joined, I really didn’t like how my drawing was shaping up, aggravated every time I peeked at what the other super-talented kids were doing. Unlike Matt, who still passed his presentation despite the odds, I was so uncomfortable with the thought of submitting a shitty artwork that I just quit without finishing my piece.

I didn’t get any pep talk about never giving up until the end. We came home, and my grandma just bluntly told me off for being a disappointment.

If you look at the other examples I gave in the intro, you’ll probably see a pattern of me being afraid to be seen in a negative light by other people. While I don’t think I was born that way, a childhood of constantly dealing with other people’s disappointment and the real consequences of it — being punished by adults for being a problem child; being made fun of and bullied for being weird; being looked down upon for being inept at basic life skills (then being compared to other kids who were adept at it); feeling unloved — would instill in me an intense fear of rejection and not living up to expectations.

I never got the support system needed to overcome that fear (as none of the adults in my life even knew about the concept of anxiety), or the mentorship needed to develop fundamental life skills like socializing or emotional resilience, so instead I dealt with it in unhealthy ways, like putting on a façade of competence, or running away from situations that would expose my lack of it. I would desperately cling to every good first impression I could make — a badass CAT Corps Commander, a good artist, a cultured hip-hop aficionado, a good cook, a proper engineer, a man who can carry a relationship — while dreading the day that the image I cobbled together falls apart, and people are once again disappointed in the real me.

Selfish as it sounds, I was so afraid of it that I would often pray for a meteor to hit the ground I was standing on. I would rather the whole world ended than just my world ended once my shortcomings were exposed.

But inevitably, it happened every time. Sometimes, I hurt and inconvenienced people because of it. But there were other times where it wasn’t as bad as I thought — the people in my life still accepted me, and I simply had to do better next time.

Living with social anxiety is like this for many people. Rejection and failure can feel like life-or-death situations, where every little mistake is punishable by public execution. General anxiety extends this overthinking to every facet of your life — your plane is going to crash; your surgery will go horrifically wrong; your loved ones aren’t returning calls because they were caught in an accident; you left the door to your house open because you can’t remember if you locked it or not; some small mistake you made at work will create a butterfly effect that would get you fired. It feels like the universe itself is out to smite you with the full wrath of Murphy’s Law.

And we see the absolute extremes of this in Matt’s story, where pairing it with depression turns it into this vicious loop of losing all joy in life then being unable to recover from that because he’s afraid of everything.

Overcoming the pain means accepting it

In any discussion about anxiety and depression, the main question is always going to be: does the pain ever go away? Do you ever go back to the way you used to be?

Matt answers that question with a candid no.

Initially, he would be riddled with guilt for becoming a burden to Andrea and his family, and with despair over how low he’s fallen. But eventually, he comes to terms that this is who he is now and he’s just gonna have to keep living despite it.

He makes the effort to become a functional adult again, like in the previously mentioned trip to the grocery store, and in his various obligations to socialize and network once he became a book author. As expected, it’s a horrible experience every time, but the important part is that he teaches his body that these uncomfortable situations aren’t as world-ending as his anxiety make it out to be. The world keeps turning, life keeps going, and he’ll have many chances to do slightly better every time.

That’s why I titled this article “adapting to anxiety and depression“, because even more than a decade after Matt’s first struggle with these conditions, it still comes back to pester him from time to time, but he’s learned to get used to it; and he’s living a busy, fulfilling life that allows him to distract himself from the pain instead of suffering from it 24/7.

Even nowadays, at age 31, I’m still thrust into situations that fill me with overwhelming anxiety, but now I’m trying my best to stick it out and get used to the feeling instead of running away. Before, I would try to sidestep the source of discomfort by developing myself out-of-sight, like when I practiced riding my bike at 3AM so no one could see me falling off and looking like an idiot. While that method worked for me and yielded results, I see now that it was still a flawed coping mechanism… because it was that looking like an idiot part that I really needed to learn to get used to, not becoming good at cycling out of nowhere.

I have a right to be imperfect and grow in the presence of other people who are also still growing; I don’t have to present an illusion that I’m some genius who’s good at everything I do.

Because I never will be, and it’s okay.

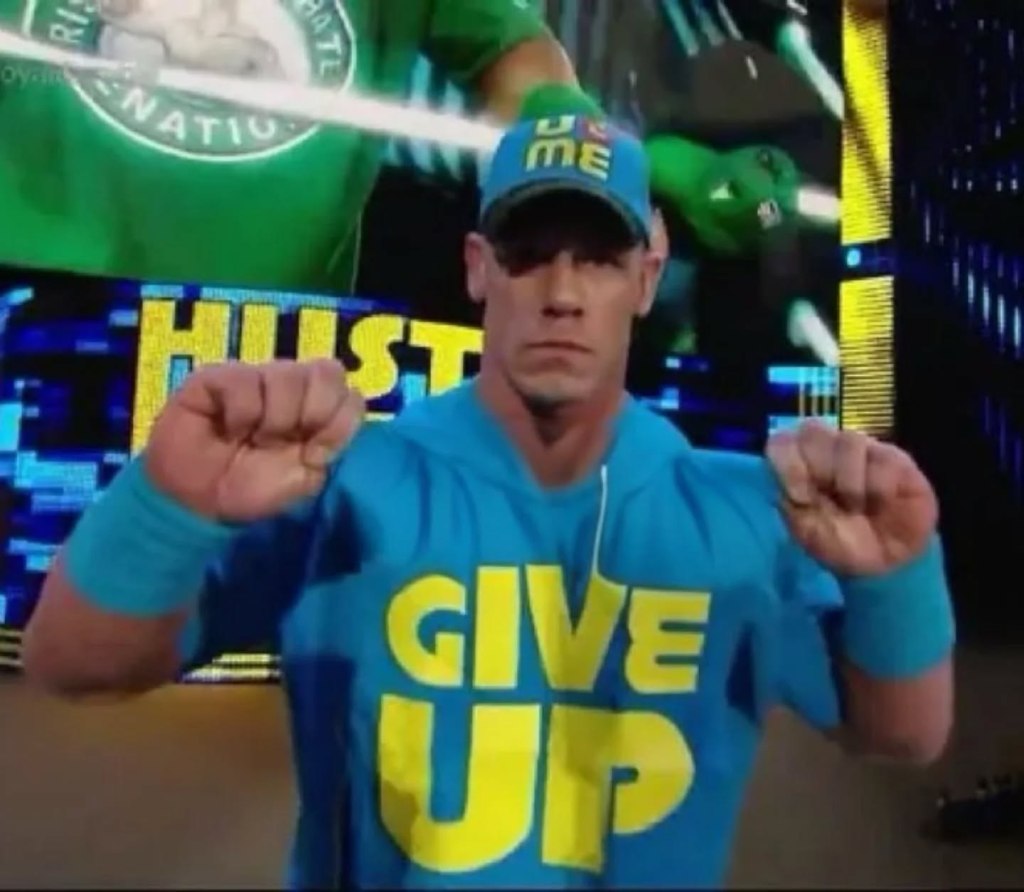

If you could have a conversation across time…

The pivotal points of the book for me would be in the three-part story, “A Conversation Across Time”, where he imagines talking to his past self (at his most suicidal) to reassure himself that everything will be okay, and there’s a bright future waiting at the end of the tunnel — where the pain is no longer as bad; where he’s learned to accept and embrace and coexist with his condition; where he has regained enough control of his life to become an author, a husband, and a father.

Initially, Past Matt is in too much pain to believe that any future exists for him, but as he makes it through life and survives each bout of depression that comes his way, he starts to become convinced.

Obviously, having this conversation with your future self is a quantum impossibility…. But what if it wasn’t?

How many of us will hit such a low point in our lives that we just become desperate for any sign that the suffering will end?

How comforting would it be to know that you will reach a point where you’re finally happy with yourself and the kind of life you’re living?

How many lives would have been saved if they only knew what their future could have been; if only they had faith that there are better days coming ahead if they can make it through the bad times?

Unfortunately, we can never know for sure; especially not when the state of the world just seems to be getting worse every day. I empathize and hurt for anyone who gives up on that fight and decides to end their suffering on their own terms. The only reason I’m not one of them is a constantly-shifting scale of fear and hope: hope that things do get better in the future rather than worse, and fear of missing out on what I can become if I can make it through these currents.

When I made it to this part of the story, I was on my birthday vacation in Tromsø, Norway. Staring at the beautiful winter mornings at Telegrafbukta (Telegraph Bay), there was such a contrast between the inner peace I felt staring at this heavenly view versus the empty resignation I felt staring at death’s invitation at Blue Grotto.

It was only 4 months apart, but I felt so happy believing that I could still have better days, because otherwise I would’ve never seen this view.

What are good reasons to stay alive?

So after much discussion about depression, anxiety, and mental health, what does a book titled as such propose to be the best reason to stay alive? Well, it’s… whatever you want it to be, really.

The smiling faces of your loved ones?

Running 5 kilometers per day?

That one song that cheers you up every time?

Getting to see the final season of your favourite show?

That one beach where you like to sit on the sand and watch the waves?

Jollibee’s Amazing Aloha Champ and Peach Mango Pie?

From these very simple happy things, to bigger dreams like buying a house, traveling the world, finding a life partner, becoming an expert at something, or changing the world for the better, the book leans on the mentality that none of us have any fucking idea what life really means, so it can mean whatever you want it to mean. If you want to believe it’s God’s grand design, go for it; pray, live with kindness, and I do hope you’ll go to heaven.

I just think life is more beautiful when it’s open-ended, and I like that Matt respects that in this book instead of selling us just one singular reason to stay alive.

I’ve seen some people criticize Matt for selling a book with such a shallow, cop-out conclusion, but I honestly don’t see what the problem with this is. Everyone lives a unique life, with unique circumstances, aspirations, and sources of joy, and everyone rearranges the top layer of their Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs according to what they care about the most.

Are we supposed to expect book authors to present us with a concrete, fully-detailed, undisputable roadmap of what the point of life should be? Only self-indulgent ancient philosophers do that, and even they’re self-aware that their opinions are subjective, and constantly question themselves on said opinions.

I would find it utterly disappointing if one man could tell me how I’m supposed to live, and how I’m supposed to fix myself if I’m not living up to that standard, so I don’t understand why critics buy self-help books to hear something like that. But I guess that’s just the kind of state of mind that depression will push you towards.

Reminder as well that “Reasons to Stay Alive” is a memoir. It’s not meant to be a guide on how to survive depression, but a testimonial of someone who’s been surviving it successfully up to this point; with the hopes of reminding you of who you are and that you find it within you, through your own unique means, to overcome your depression.

Criticisms over “anti-medication” sentiments and white privilege

Another criticism I’ve seen people online levy towards Matt is that he’s anti-medication, but I didn’t really see it that way from my reading. He makes clear remarks across the book that he recognizes the importance of medication; he emphasizes that he would never invalidate the experiences of the many people who have been helped by pills, just that it wasn’t working for him, so he preferred to deal with his depression without it.

The only thing a person can talk about with authenticity is their own personal life experiences, so of course Matt would lean on that — focusing on how he felt when he tried to take diazepam and why it discouraged him from continuing to take other meds. That’s not the same as saying that they don’t work, period.

I think Matt has done his due diligence of recommending the proper channels on how to seek professional help for depression, and an endorsement of that is an endorsement of whatever kind of treatment they’ll provide you, which includes medication.

One other criticism I saw is that he had a lot of privileges that helped him overcome his depression the way that he did. He was very lucky to have a partner like Andrea who had never-ending patience for him even as his condition worsened; who was constantly there to be his safety net as he took baby steps to slowly become a functional adult again; who was so sure of him as her future husband that she stuck it out even as he looked like a shadow of his former self. He was very lucky to have her and his loving parents as his financial and emotional pillars while he struggled to get his life together.

Too many lower-to-middle-class commonfolk don’t have this same robust support system, especially if they come from a culture that’s not yet as well-informed about mental health. A breadwinner with an onsite job or multiple jobs can’t afford to just suddenly put their life to a halt due to panic attacks and social anxiety; they can’t afford to be so vulnerable (as much as they have the right to) when loved ones are depending on them for strength and resilience; their economic class prevents them from having access to the necessary professional help they need, or from having the time for yoga and meditation or the money for gym and vegetables (it is a travesty how expensive fruits and vegetables have gotten nowadays).

And they certainly don’t have the luxury of leisurely going back and forth between Spain, England, France, or wherever for their mental health journey.

*Scott Steiner voice* Add discrimination to the mix, and the issue becomes drastically more complicated.

While I see where they’re coming from, I don’t think Matt intended to highlight his white privilege in such an insensitive way. His condition — severe anxiety of being anywhere in the outside world — can happen to anyone regardless of social class, and he made a conscious decision to keep his opinions grounded, research-based, and mindful of the fact that everyone will have their own unique mental health journey that’s within their means.

But he’s also self-aware of his stature in life, so in order to be authentic, he leans on his side of the fence: talking about how even people of privilege and celebrities struggle with depression despite the resources they have; how difficult it can be when people guilt you into feeling like who have no right to be suffering from depression because you have a better life than others, therefore you’re supposed to be happy. You have the resources to deal with your mental illness unlike us, why aren’t you better? These are unfair sentiments to hear from people who are mentally sound, but even more disappointing to hear from the online mental health community itself, who I thought would find solidarity through shared struggle.

While I can’t fully relate to Matt’s living conditions, I can still see enough similarities between our struggles to empathize with what he’s gone through. I think he’s shown enough self-awareness in the book to not sound tone-deaf, and I respect his due diligence with citing credible sources like the World Health Organization for all of the studies he put in the book. And personally, even if his story has a hint of privilege to it, I’d rather someone speak of their experiences with authenticity than pander to a wider demograph about a struggle they never had.

Conclusion

Overall, I really appreciate having read “Reasons to Stay Alive“. Perhaps I enjoyed it a lot more than other people did because I came into it without any expectations of learning revolutionary new information I hadn’t read elsewhere before, or that the book would fix my life. The struggle with anxiety just hit very close to home with me; the timing of reading the book simply aligned with my current journey of healing, and I found a kindred spirit who inspired me to believe that I can untangle my life and make it through this storm.

It’s also given me validation for all those years in my life that I struggled with seemingly normal human activities because of anxiety, and renewed my appreciation for how far I’ve come since then.

Despite my impostor syndrome, I’ve grown to genuinely love every endeavor I’ve undertaken. I’m not as good at cycling as people who’ve done it all their lives, but I truly enjoy the meditative experience of riding against the wind. I may have only learned to cook from YouTube, but I genuinely enjoy making loved ones happy through my dishes. And I may have crash-coursed my way through hip-hop ‘expertise’, but I genuinely love the genre and it has allowed me to find beauty, poetry, and solidarity in the grimy realities of the oppressed.

And despite my social anxiety, I’ve somehow made a surprisingly decent amount of friends who see me and accept me for who I am, which my ex (whom I’ve also found closure with since the time I started writing this article) demonstrated to me when she arranged for my surprise birthday party last year. Some of these friends have been a big help in this healing journey of mine; some of them I try not to bother with this stuff, but I know that we’re all rooting for each other’s happiness and success.

I lost sight of these things for a while. But I remember it now. And that makes me happy.

I don’t know yet what the future holds; how bad the current state of my anxiety really is (relative to what qualifies for a GAD diagnosis), or what I’ll learn about myself once I continue therapy. But just from gauging my feelings alone, I feel hopeful that I can make it through this constant torrent of painful emotions and negative thoughts, and that I’ll keep finding more reasons to stay alive if I just keep moving forward.